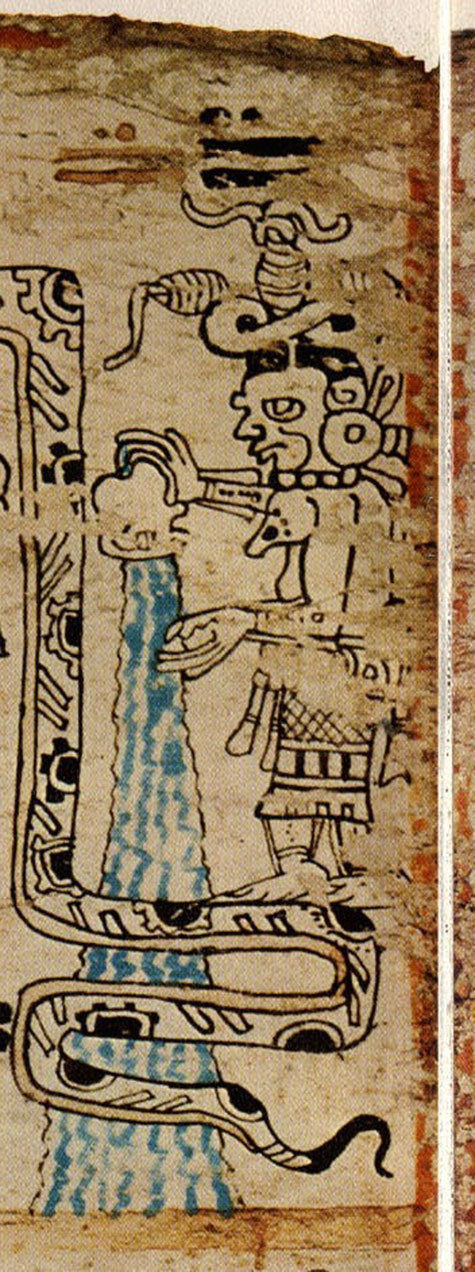

Chac-Chel, the aged mid-wife goddess weaving on a backstrap loom. Scholars interpret the loom weaving to be the placenta, and thread the umbilical cord.

Madrid Codex 79c

The Maya Goddess Ix-Chel has long been revered as the quintessential Moon Goddess of the Maya civilization, inspiring pilgrimages, new-age ceremonies, and a surge of imagery portraying her as a youthful bestower of fertility, abundance, weaving, and healing. This depiction of the goddess as a radiant and fertile figure resonates with Western audiences, whose perspectives have often been influenced to revere youthful femininity over that of elderly women. Consequently, Ix-Chel came to symbolize a sort of elixir of vitality. It is unfortunate, as this portrayal of a singular Maya Goddess has perpetuated a romanticized falsehood, erasing important cultural nuances of the Maya civilization. The repercussions of this distortion are difficult to retract in a world where verifiable evidence is sometimes sidelined, and modern practitioners assert the authenticity of "oral" traditions, regardless of their divergence from the sources they were mistakenly based on. The result has been the commercialization of Ix-Chel by various companies who appropriate her image for marketing medicinal products and spiritual experiences, which only amplifies this issue.

So who is responsible for this myth? There are two major contenders behind the naming of Ixchel as the most important goddess, and minor influences who served to confirm it indirectly.

The two most influential authors are the formidable Spanish Franciscan Friar Diego de Landa, who infamously burned at least 27 Maya Manuscripts at Mani in Yucatan on July 12, 1562, alongside other atrocious acts against humanity; and the British Archaeologist Sir Eric S. Thompson, whose scholarly and popular works on the Maya spanned from 1939 to 1970. While it is valid to argue that judging historical figures through a modern lens can be problematic, it is equally crucial to unpack the reasons behind their erroneous conclusions. Understanding how the cultural norms and biases of outsiders influenced authentic indigenous knowledge is essential to decolonizing cultural myths.

Friar Diego DeLanda

Izamal, Yucatan Mexico

Photo by Jennifer Bjarnason May 2007

Spanish Franciscan Friar Diego de Landa (November 2, 1524 – April 29, 1579) faced formal charges as a war criminal for his egregious actions against the Maya population. In 1563, by order of Bishop Toral, he was extradited to Spain to stand trial for his transgressions. To win favour from the Church, Landa was compelled to recount his knowledge of the Maya culture, by writing a work titled "Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán" (A Relation of Events in Yucatán), which he completed in 1566. A short but fascinating read, Landa`s book represents a complex paradox of biased perspective alongside detailed observations that form the foundation of our understanding of the Maya, including their complicated calendar system. Praised by many scholars as an ethnographic masterpiece, Landa's book offers comparable significance for the Maya culture that the Rosetta Stone holds for Egypt. While the original manuscript vanished, a copied rendition resurfaced in 1660. Nonetheless, its contents remained concealed from the public eye until 1862, an interval spanning nearly three centuries from its initial inception.

Within this document, Landa makes reference to the presence of multiple unnamed gods and goddesses in Maya cosmology. In his interpretation, Ixchel is an evil sorceress, associated with childbirth and fertility. Notably absent from his description, however, is any reference to the moon:

‘So many idols did they have that their gods did not suffice them, there being no animal or reptile of which they did not make images, and these in the form of gods and goddesses . . . at the time of accouchement they went to their sorceresses, who made them believe all sorts of lies, and also put under their couch (birthing-bed) the image of an evil spirit called Ixchel, whom they call the goddess of childbirth . . . there were many who in times of lesser troubles, labors or sickness, hung themselves to escape and go to that paradise, to which they were thought to be carried by the goddess of the scaffold whom they called Ixtab’. (Gates’ translation of Landa 1978: 47, 56, 58)

Landa also observed ceremonies of goddess worship on the island of Cozumel, however, he noted that the women were unable to explain Ixchel`s significance. Linguistic interpretations of her name include "one who is pale-faced," thought to allude to the moon, or "lady rainbow," a translation favored by many linguists due to its correspondence with "Chac-Chel," signifying "Great Rainbow." One notable difference between the depictions of the goddess depictions of Cozumel and elsewhere, is the inclusion of a waning moon. When John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood visited the shrine-ruins on Cozumel Island in 1841, they discovered an abandoned site devoid of any traces of religious activity.

Today, the island attracts annual new-age pilgrimages, and since 2018, Pueblo del Maiz has organized a yearly festival dedicated to the celebration of Ix-Chel.

The modern representation of Ix-Chel holding a flower finds its origins in an ancient hieroglyph depicting a woman positioned before her loom. Over time, this portrayal underwent alterations. The tree once depicted before her disappeared, and the loom was substituted for a flower. Notably, her breasts are depicted as youthful and firm, a departure from the original illustration that depicted saggy breasts.

Although Landa mentioned Ix-Chel (along with Ixtab, the "suicide goddess") by name in his document, he left out the names of other goddesses he witnessed in religious practices, likely because he did not know their names. It should be said that though Landa was charged for war crimes, he remained a fearless explorer, wandering to parts of Yucatan noone else would go. Upon witnessing the near sacrifice of a young boy, he intervened, rescued the boy from being killed, and began to preach. Though conversion policies are validly criticized for interference and eradictation of cultural history, it´s also understandable why any outsider would find the act of child sacrifice to be abhorent. Though it cannot justify nor excuse the subsequent cruelties of Landa against the Maya, it is easy to conclude that his personal experiences shaped his disdain for a culture whose nuances he misunderstood (human sacrifices were not made to Ixchel, as far as we know, yet he brandished her as evil). At least we can thank Landa for paying special attention to the Maya Calendar system, as his detailed explanation is why modern academics can decipher it. Following the death of Bishop Toral, Landa was exonerated of wrong-doing and sent back to New Spain as the Second Bishop of Yucatan.

Chac-Chel with water pouring from her underarms and vagina, surrounded by animals including a rabbit and jaguar cub. The bottom right is Chac Mul, who is often pictured with Chac-Chel

Between the time of Landa, and the arrival of British Archaeologist Sir Eric S. Thompson (December 31, 1898 - September 9, 1975), nothing was documented about Ixchel or other goddesses of the Maya world, leaving a time gap of 300 years. Unlike Landa, Thompson had a keen fascination of the Maya, and was who inadvertently amalgamated attributes of various Maya goddesses into a singular "all-powerful" female figure, effectively popularizing the romantic myth of Ix-Chel. Despite Thompson's significant contributions to Maya studies, his era was still characterized by the marginalization of women in popular culture. This norm is evidenced in even the most magical literature, such as J.R.R. Tolkien's beloved "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy, published in 1954, which features only three female characters with limited roles. It stands to reason that the absence of women in influential spheres such as politics, literature, and positions of authority during Thompson's time influenced his interpretations of the female depictions in Maya iconography and cosmology, especially as modern academia shows the Maya held a reverence for women, despite being organized under patriarchy. While the Maya concept of the toothed vagina demonstrated either fear or awe of women, their depictions of women with their water breaking, of their wombs and umbilical cords, as life-givers, as powerful, sexual and of having equal participation in creation paints a very different acknowledgement of women in Maya society, as compared to their European counterparts of that time.

This historical context may also shed light on why Landa, in his numerous observations of Maya ceremonies, did not delve into a thorough examination of female goddesses, with his deeply conservative religious beliefs leading him to demonize Ixchel in a negative light. Such perceptions align with an era marked by the suspicion cast upon women of European society, which in Landa`s time was manifesting in the infamous witch trials and unjust execution of innocent women.

In the context of contemporary new-age ceremonies, where oral traditions are shared with tourists, claims of accessing ancient Maya wisdom or practices can be disingenuous. The time gap between the authentic ceremonies before and during Landa's era and those conducted today renders the reliance on Sir Eric S. Thompson's much later observations misguided. Nevertheless, these claims may function as a cultural placebo and offer a path for individuals seeking feminine spiritual healing. As is often the case with new-age spiritual concepts, the underlying intent is to recover what colonialism obliterated. Within this pursuit, it remains imperative to discern the origins of indigenous knowledge and recognize how it shapes present-day conversations.

Ixik Kab from the Dresden Codex

So, if Ix-Chel isn't the sole Maya Goddess of the Moon, then who is the young goddess she has been mistakenly associated with? The Dresden Codex introduces us to Ixik Kab, a deity of the Earth, who is often depicted with a waxing moon. Interestingly, a simple Google search might yield references to her as the Goddess of the Moon. However, those who have closely examined the information within the Dresden Codex will discover that she is not, in fact, a Moon Goddess. Scholars surmise the waxing moon is an indication of Ixik Kab`s youth and fertility, rather than as her role as governess of the moon. The moon's influence over tides and women's menstrual cycles aligns with this symbolism. Moreover, the name "Ixik Kab" translates to Earth Mother, rather than Moon Goddess. It's worth noting that the Maya possess numerous tales concerning the moon, and various gods and goddesses are designated for specific roles. Additionally, there is mention of another goddess named Ixik Uh, meaning Lady Moon, who may potentially be linked to Ixik Kab, given the Maya's inclination for duality within their cosmology.

In contemporary archaeological discourse, Ixik Kab is now differentiated from Ix-Chel and Chac-Chel using the names "Goddess 1" (Ixik Kab) and "Goddess 0" (Chac Chel), the latter being viewed by many as a distinct designation or a counterpart to Ix-Chel.

Chac Chel with an upended water jug and serpent. The water could symbolize fertility, or a destructive flood.

Archaeological artifacts linked to Chac-Chel have been unearthed at various sites, spanning from Chichen Itza and the nearby Balancanche Cave, to a mural at Tulum and the influential city of Yaxchilan. The extent of her reach is exemplified by discoveries as distant as the Margarita Tomb of Copan in Honduras. Notably, one figurine from the Island of Jaina, Campeche, is believed to embody Chac-Chel in a warrior form (depicted below), and she stands as a prominently depicted figure within the Madrid and Dresden Codices. The Maya concept of duality lends a multifaceted nature to Chac-Chel, whose name translates to "Great Rainbow." This duality allows her to preside over realms such as childbirth, weaving, medicine, and fertility, while simultaneously being associated with themes of destruction, floods, and endings. Within the Maya belief system, rainbows bear an ominous significance, believed to be the flatulence of demons and sources of seizures. According to some beliefs, individuals who meet a tragic end are compelled to wander the earthly plane in torment for four years, with rainbows signifying their tormented souls.

Frequently depicted alongside the Rain God Chac-Mul, Chac-Chel also assumes the role of the female counterpart to creation and serves as the consort of Chac. This interplay further blurs the narrative, as Ixchel was married to Itzamna, who assumes the mantle of the Sun God. The conundrum emerges: if Ix-Chel and Chac-Chel are indeed one and the same, how do we reconcile their disparate unions? Could it be a matter of divergent interpretations across different regions? Could Ix-Chel embody all things positive, while Chac-Chel represents her negative counterpart? While the answers may elude us, future scholarship may yet bring clarity to these complexities, ultimately laying to rest the enduring myth of the romantic and all-powerful Moon Goddess Ix-Chel.

Thanks to those of you who have supported my writing and research through your donations. A little adds up to a lot, and helps cover my time so I can keep publishing these articles. If there's a subject you'd like to see covered, please email me! If you would like to make a small donation of $20 Pesos (Approximately $1.20 US), please click here: DONATE

Late Classic figurine of Chak-Chel from Jaina, Campeche Mexico represents her as an elder and a warrior

REFERENCES

Bulletin (Kalamazoo Institute of Arts) no. 14 (Dec., 1964). "3000 Years of Pre-Columbian Art," cat. no. 82 (illus.).

Ardren, T. (2004). Where are the Maya in ancient Maya archaeological tourism? Advertising and the appropriation of culture. In Y. Rowan & U. Baram (Eds.), Marketing heritage: Archaeology and the consumption of the past (pp. 103-13). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Coe, M. D., & Koontz, R. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs (6th ed.). New York: Thames and Hudson.

Coe, M. D. (2005). The Maya (7th ed.). New York: Thames and Hudson.

Landa, D. de (translation by William Gates). (1978 [1566]). Yucatan before and after the conquest. New York, NY: Dover.

Miller, M. E. (1975). Jaina Figurines: A Study of Maya Iconography. Princeton: The Princeton University Art Museum.

Miller, M., & Taube, K. (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Our publication is 100% free, but if you are feeling generous and would like to make a small, voluntary donation to help us cover our time for research and writing, please click below for payment options starting at $20 MXN (Approximately $1.20 USD). Thank you!

fascinating text